A 1,500-Year Legacy in Every Sheet

Kyúdaime Ichibé Iwano, designated a Living National Treasure, is the bearer of a tradition that has lasted over 1,500 years—Japanese papermaking. His lineage even crafted Fukui Hansatsu, one of Japan’s earliest forms of paper currency. Today, Iwano’s paper is sought after not only for traditional use but also in the world of fine art, where it endures up to 200–300 passes of ink rubbing in mokuhanga (woodblock prints) without damage. His washi possesses a rare duality—soft enough to absorb pigment repeatedly, yet strong enough to withstand hundreds of printings.

The Power of Washi: A National Heritage

Japanese handmade paper, or washi, includes three major types: Echizen washi from Fukui Prefecture, Mino washi from Gifu, and Tosa washi from Kōchi. Echizen’s most prized variety is Echizen Kizuki Hōsho, made exclusively from kōzo (mulberry) fibers and said to last over a thousand years. This durable paper, used for woodblock printing and the restoration of fine art, derives its strength and flexibility from its core material—Daigo Nasu kōzo from Ibaraki Prefecture, known for long, supple fibers that separate easily during processing.

Papermaking by Instinct: Precision Without Machines

“I once thought the tradition would end with me,” Iwano muses, “but lately there’s no time to rest. Washi is gaining attention again.” When we visited his workshop, he was crafting sheets bound for France. “It used to be easier to make paper after the equinox, but summers are hotter now. The neri (sticky extract from tororo-aoi) weakens quickly in the heat.”

He demonstrates the delicate balance of neri—a mucilaginous agent essential for even fiber dispersion in water—adding it carefully to the vat. “There’s even a folk song: ‘Started learning at age seven or eight, still don’t know how to mix the neri right.’” In summer, the viscosity fades fast, but winter brings ideal consistency, letting Iwano work steadily without adjustments.

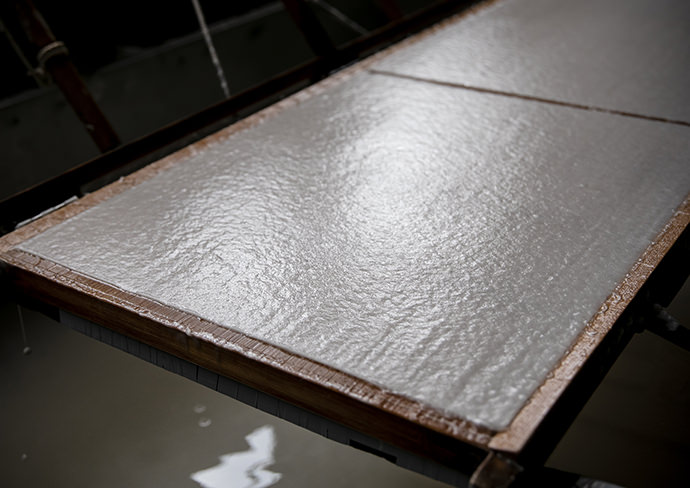

On this particular day, he was producing paper just 0.2 mm thick using the nagashi-zuki method—pouring and layering pulp over a bamboo screen. Guided only by his trained senses, he adjusts the thickness in 0.1 mm increments, a feat of craftsmanship impossible to replicate by machine. For thicker business card stock, he uses the tame-zuki method, scooping a concentrated mix of kōzo and neri into the screen and spreading it slowly, forming a dense, textured finish.

Iwano’s washi has become a vital part of art restoration at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The museum orders three types: 0.1 mm, 0.2 mm, and 0.3 mm thick. “Five or six years ago, they reached out. I declined at first—I was already overwhelmed with domestic orders. But they insisted, saying my paper was unmatched for conservation.” Since then, over 200 sheets are shipped annually to France.

After testing paper samples from around the globe, the Louvre declared Iwano’s washi the best for restoration. It is made solely from natural kōzo, without any chemical treatments, resulting in a neutral pH—neither acidic nor alkaline. This quality ensures longevity, strength, and versatility. In fact, restorers can peel a single sheet into layers for delicate applications, making it ideal for conservation.

The Hidden Ingredient: Water from 30 Meters Below

What makes Iwano’s paper truly unique is the water. Drawn from a 30-meter-deep well beneath Echizen, the soft, neutral water contains no iron and minimal impurities. “Even if you use the same kōzo and the same method,” he explains, “you can’t make the same washi without this water. My technique isn’t special—it’s the water, the tradition of making only Echizen Kizuki Hōsho, and the invisible inheritance passed from parent to child.”

With a calm and humble expression, Iwano speaks like the water itself—gentle, patient, and clear. Through his hands flows not just pulp and fiber, but the quiet spirit of a thousand years of Japanese artistry.

Photographs by: https://www.the-kansai-guide.com/ja/article/item/20020/, https://cappan.co.jp/washi/paper/echizen/

コメントを残す